Rachel: I just started reading it. You didn't mention that the heroine looks human but is actually a giant bug!

Rachel: She has no heart, no blood, and no circulatory system! Because she's a bug.

Sholio: A bug with boobs, which you will be hearing about at length.

Rachel: I look forward to the explanation of the boobs' existence. Or maybe I don't.

Also, there are orders of mice priests. I am unexpectedly charmed.

Rachel: Ah. The bugs lactate, due to "a quirk of evolution."

Rachel: I just hit the respectful pronouns for zombies.

Rachel: And the question of whether the word zombie is culturally appropriative.

Sholio: Worrying about zombie pronouns is exactly how you get eaten in the zombie apocalypse.

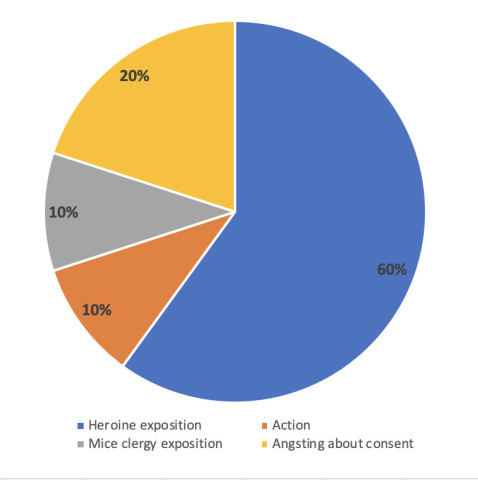

Rachel: I am at the 50% mark of the Seanan McGuire book and 60% of it is the heroine delivering exposition, either internally or to the other characters who don't remember her. Another 10% is the mice clergy delivering exposition. This is surprisingly entertaining. So far this is the only Seanan McGuire book I have ever actually enjoyed.

The rest consists of 10% action and 20% angsting about consent.

Sholio: This makes me want to make a pie chart.

This is book 10 of an 11-book series, so the massive amounts of exposition were more interesting than they would have been had I read the previous nine books.

Sarah Zellaby is a "cuckoo," from a race that evolved from wasps and are generally sociopaths who dump their children into human families; the cuckoo children invariably murder those families. Sarah is one of only two known non-sociopathic murderer cuckoos. She is telepathic and can mind-control people, so her human adoptive parents drummed it into her that consent is the highest value, with respect for others a close second. This results in her being very concerned over things like not misgendering zombies who are currently attacking her, plus a tendency to martyr herself.

She ends up stranded on another planet, along with a college campus, assorted students, a bunch of zombie cuckoos, and several friends and family members, one of whom is her true love (they're not biologically related), none of whom remember her due to magic but all of whom do remember that cuckoos are very dangerous. Hence the First Half of Exposition.

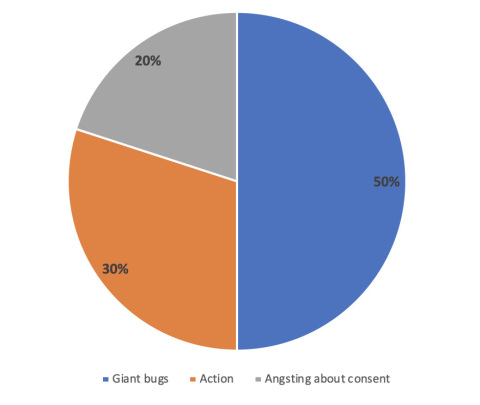

The second half of the book is about 50% giant bugs, 30% action, and 20% angsting about consent.

It heavily features giant flying millipedes, an extremely adorable giant spider, and plenty of angsting over the ethics of mind-controlling non-sapient giant bugs. Sadly, the mouse clergy get forgotten about for most of it.

I enjoyed this book despite a number of odd quirks of the sort that normally put me off McGuire's books. The heavy-handed lecturing about consent actually made sense for this character and her situation. Other quirks were just peculiar, like the breast thing. Female characters comment on their own breasts a lot. Sarah is obsessed with finding a bra for the first third of the book. I get that she specifically would feel very uncomfortable without one, presumably because she has behemoth bug boobs, but she narrates at great length about how ALL women need bras, that sports bras are not real bras (apparently underwire is superior - not an opinion I share), and that ALL superheroines would want to wear bras at all times.

I will just say that for most of 2020, when lots of people did not have to go anywhere, most of the women in my apartment complex, myself included, did not wear bras most of the time.

The book has a novelette at the end narrated by Annie, who turned out to be insufferable as a POV character, so much so that I only got a few pages in. In general, I really liked Sarah, the mouse clergy, and the giant bugs, but I was not so big on her family. So while this individual book was fun, I probably won't be continuing with the series.